Casting vs Forging: How to Choose for Engineering Machinery Parts

2026.01.02

2026.01.02

Industry news

Industry news

Casting vs Forging: What Changes in the Metal (and Why It Matters)

When customers ask “casting vs forging,” they are usually trying to reduce field failures and total cost—without over-specifying the part. Both processes can produce reliable components, but they create very different risk profiles for heavy-duty engineering machinery where loads are cyclic, impact-driven, and often contaminated by dust, slurry, or corrosion.

In simple terms, casting forms a part by pouring molten metal into a mold and letting it solidify, while forging forms a part by plastically deforming heated metal under compressive force (hammer or press), often within dies. That “how it’s formed” difference strongly influences internal soundness and consistency.

Practical implications you can expect in production

- Castings can achieve complex geometry efficiently (ribs, pockets, internal cavities), but they are more sensitive to solidification-related defects such as shrinkage and gas porosity.

- Forgings typically deliver higher density and stronger directional structure (often described as improved “grain flow”), which generally improves fatigue and impact resistance for load-bearing machinery parts.

- Both routes almost always require downstream steps—machining, heat treatment, and surface finishing—to meet tight tolerances and service-life targets.

The correct choice is therefore less about “which is better” and more about aligning process capability to the dominant failure mode: fatigue cracking, impact fracture, wear, distortion, leakage, or corrosion.

Performance Under Real Loads: Fatigue, Impact, and Wear

Engineering machinery components often experience combined loading: torque + bending + shock + vibration. In this environment, “average strength” matters less than consistency and damage tolerance. This is where casting vs forging decisions most directly affect uptime.

Fatigue: the most common long-term failure driver

Fatigue cracks typically initiate at stress concentrators (fillets, keyways, bores) and at micro-defects. Because castings can contain shrinkage porosity or inclusions if process control is not excellent, fatigue life can show wider scatter. Forging, by contrast, commonly offers a more uniform internal structure, reducing “unknowns” when the component is repeatedly loaded.

For example, a gearbox swash plate forging is a part where stable performance depends on dimensional accuracy and resistance to cyclic hydraulic and mechanical loads. In applications like excavators, the cost of a fatigue-driven breakdown is not the part price—it is machine downtime, secondary damage, and logistics.

Impact and shock loading: when toughness becomes the selection gate

Undercarriage, traction, hooking, and drive elements are frequently exposed to sudden impact loads (rock strikes, start/stop torque spikes, abnormal operator behavior). In these cases, the safer strategy is to prioritize toughness and defect tolerance. When the consequence of brittle fracture is high, forging is typically the lower-risk starting point because compressive deformation and post-forge heat treatment can be engineered to meet demanding toughness targets.

Wear and surface durability: where heat treatment and finish dominate

Wear resistance is rarely solved by process choice alone. It is achieved through a combination of alloy selection, heat treatment (quench/temper, case hardening where appropriate), and surface finishing (shot blasting, grinding, protective coating, or passivation for stainless). Forgings frequently integrate well with these steps because the base material is dense and responds predictably during heat treatment and machining.

Geometry and Function: When Casting Can Be the Better Engineering Choice

Casting is not “inferior”—it is optimized for different design priorities. If your part needs complex internal features, large cavities, or thin-wall sections that are impractical to forge, casting may deliver the best manufacturability and cost.

Design features that favor casting

- Internal channels or complex voids that would require extensive machining from solid stock.

- Highly integrated shapes intended to reduce assembly operations (multiple functions in one body).

- Very large components where forging equipment capacity is a constraint and load requirements are moderate.

A practical approach used by many OEMs is “design-for-risk”: cast where geometry is dominant and loads are moderate; forge where loads and fatigue dominate and geometry is straightforward. If your component sits in the drivetrain, undercarriage, or torque path, the process selection often shifts toward forging even if casting appears cheaper on unit price.

Defects and Inspection: What Buyers Should Control in the RFQ

The most expensive quality problems are the ones you do not specify until after a failure. Whether you choose casting or forging, the RFQ should convert “quality expectations” into measurable controls: inspection method, acceptance level, and traceability.

Common defect risks to plan for

| Topic | Casting focus | Forging focus |

|---|---|---|

| Internal soundness | Control porosity and shrinkage; validate with radiography/UT where required | Control laps, folds, and internal bursts; validate with UT for safety-critical parts |

| Surface integrity | Manage surface inclusions and sand/scale; machining allowance planning is important | Manage scale and decarb; shot blasting/grinding can stabilize surface condition |

| Dimensional stability | Control solidification distortion; expect post-process machining for tight fits | Control forging + heat-treat distortion; define datum strategy for machining |

| Mechanical properties | Property scatter can be higher if defects vary; specify test coupons/locations | Properties are typically more repeatable; specify heat treatment and hardness window |

From a buyer’s perspective, the most effective quality lever is to require an inspection plan aligned to the failure mode: UT for internal discontinuities where fatigue is critical, magnetic particle or dye penetrant for surface cracking risk, plus hardness and microstructure verification after heat treatment.

Cost and Lead Time: Comparing the Real Manufacturing Path

Unit price comparisons can be misleading because they often ignore secondary operations and quality risk. The better comparison is the full manufacturing path: tooling + raw material + forming + heat treatment + machining + inspection + scrap risk.

Where costs typically come from

- Tooling: cast molds and forging dies are both real investments; forging dies often pay back faster when volumes are stable and quality requirements are high.

- Machining: castings can reduce machining if the geometry is near-net, but machining may increase if extra stock is needed to “clean up” surfaces or remove defects.

- Scrap and rework: a small increase in defect-driven scrap can erase any nominal savings, especially on high-value machining.

If you are sourcing parts in the load path (gear carriers, traction elements, drivetrain interfaces), it is often more economical to start from a forging because you reduce the probability of defect-driven failures after machining and heat treatment. This is one reason many OEMs standardize forged blanks for critical systems and then machine to final tolerance.

If you are evaluating suppliers for forged blanks or finished parts, it is useful to review their process chain in one place (forging + heat treatment + machining + inspection). For reference, our engineering machinery forgings program is designed around that integrated route so that dimensional targets and mechanical properties are developed together rather than in separate subcontract steps.

A Practical Selection Checklist for Casting vs Forging

Use the checklist below to make the decision in a way that engineering and procurement can both support. It is designed to prevent two common mistakes: choosing casting for a fatigue-critical part, or choosing forging when the geometry is the real driver and loads are moderate.

- What is the dominant load: cyclic fatigue, single-event impact, or static load?

- What is the consequence of failure: nuisance leak, downtime event, or safety-critical hazard?

- Does the part require internal cavities/complex geometry that cannot be economically machined from a forging?

- Are you willing to specify and pay for NDT to control defect risk (UT/RT/PT/MT)?

- Will the part be heat treated, and do you have a defined hardness or microstructure window?

- What volume profile do you expect (pilot, ramp, steady-state), and how sensitive is the program to tooling amortization?

Rule of thumb: if the component is in the torque path or undercarriage and sees repeated load cycles, forging is usually the more robust baseline; if geometry complexity dominates and loads are moderate, casting can be the more efficient baseline.

Applying the Decision to Typical Engineering Machinery Parts

Below are examples showing how the casting vs forging choice is commonly made for parts that resemble what many construction and earthmoving OEMs source. The point is not to force one answer, but to show how failure mode and geometry steer the decision.

| Part example | Typical decision direction | Why |

|---|---|---|

| Gear carrier / torque-transmitting hub | Forging favored | High cyclic loads; low tolerance for internal defects; needs stable heat treatment response |

| Swash plate / hydraulic drive interface | Forging favored | Fatigue + precision; distortion control through integrated heat treat + machining plan |

| Complex housing with internal passages | Casting favored | Geometry-driven; expensive to machine from solid; casting can reduce operations |

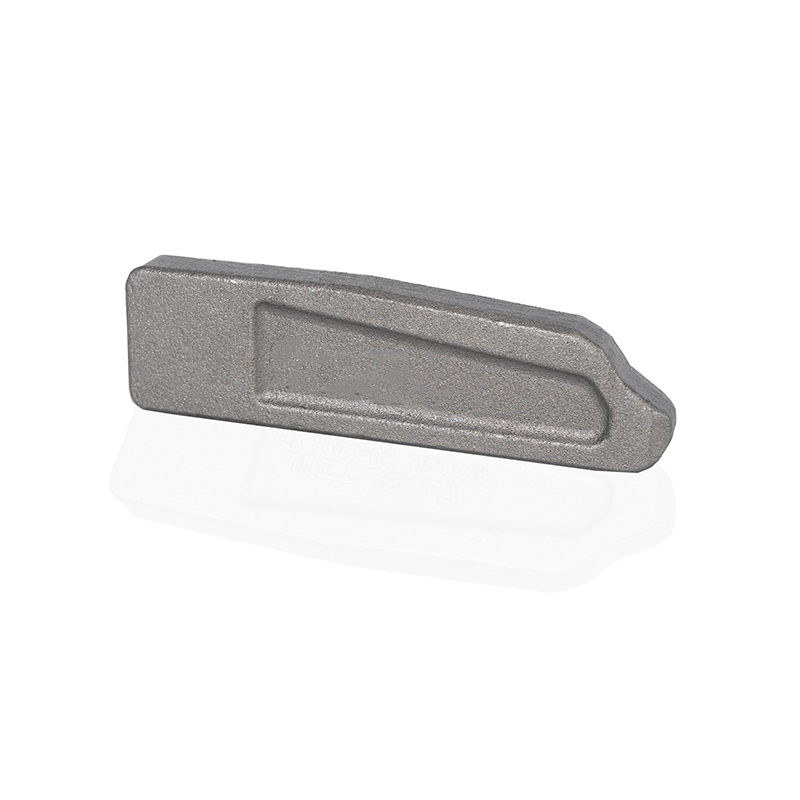

| Wear plate / scraper-like component | Depends on wear strategy | If impact + fatigue are high, forging + heat treat helps; if geometry is simple, cost may dominate |

As a concrete reference, we commonly see forged engineering machinery parts in the single-digit kilogram range where fatigue and impact performance justify a forging baseline—for example, components like a paver hopper conveyor scraper at 5.5–7 kg or an excavator gearbox swash plate at 3–5 kg, where material choice and downstream processing are engineered for service conditions rather than only initial cost.

Turning the Choice into a Reliable Supply Program: What We Provide as a Forging Manufacturer

Once forging is selected, the next risk is execution: inconsistent heating, uncontrolled deformation, or weak integration between forging, heat treatment, and machining. A qualified supplier should be able to show how each step is controlled and how inspection verifies the critical characteristics.

Our approach is to keep the core steps within one controlled manufacturing chain—mold processing, sawing, forging, heat treatment, machining, inspection, and packaging—so that metallurgical targets and dimensional targets are not managed in isolation. This is particularly important for parts like the planetary gear carrier forging, where torque transfer, fit, and fatigue performance are linked to both heat treatment and final machining datum strategy.

Capacity and downstream capability (useful for buyers managing risk and lead time)

- Forging scale: nine forging production lines with stated annual capacity of 25,000 tons for stable series supply.

- Heat treatment: five heat treatment lines plus stainless solution equipment with stated annual capacity of 15,000 tons, supporting strength/toughness/wear targets.

- Machining: 34 CNC lathes and eight machining centers, supporting consistent datums and tolerances up to finished-part delivery.

If you are scoping a new part, a practical next step is to share the load case, target material (carbon steel, alloy steel, or stainless), and any inspection requirements. We can then advise whether open-die, closed-die, or impression-die forging is the most economical route and whether additional finishing (shot blasting, grinding, coating, or passivation) is needed to match the environment. Details of our standard offerings are listed under custom engineering machinery forgings, which can be used as reference parts when creating your RFQ package.