Hot Forging vs Cold Forging: Key Differences and When to Use Each

2026.01.30

2026.01.30

Industry news

Industry news

Hot forging is usually the better choice for larger or more complex shapes and tougher alloys, while cold forging is the better choice when you need very tight tolerances, excellent surface finish, and high-volume production of smaller parts. The “best” method comes down to geometry, material, tolerance/finish targets, and total cost after any required machining or heat treatment.

Hot Forging vs Cold Forging at a Glance

| Decision Factor | Hot Forging | Cold Forging |

|---|---|---|

| Workpiece temperature | Above recrystallization (steel often ~1000–1200°C) | Near room temperature (sometimes “warm” is used between) |

| Forming force | Lower (metal flows easier) | Higher (needs stronger presses/dies) |

| Dimensional accuracy | Good, but typically looser due to scale/thermal effects | Very tight (diameters commonly around 0.02–0.20 mm depending on part/process) |

| Surface finish | Rougher; oxidation/scale common | Smoother; can reach ~0.25–1.5 µm Ra in many cases |

| Part size & complexity | Best for larger, thicker sections, and complex flow lines | Best for smaller to mid-size parts; some geometries are limited by force and die wear |

| Typical products | Crankshafts, connecting rods, gears, heavy brackets | Bolts, screws, rivets, collars, small gears, fasteners |

If you’re deciding quickly: choose hot forging when shape and material formability matter most; choose cold forging when tolerance, finish, and minimized machining matter most.

How Each Process Works in Practice

Hot forging workflow

Hot forging heats the billet above the metal’s recrystallization temperature so it deforms without significant strain hardening. For steel, forging commonly happens around 1000–1200°C, which helps the metal flow into deep features and large section changes with less press tonnage.

- Heat billet, transfer to dies, apply compressive force (press or hammer).

- Trim flash/scale (if present), then cool with controlled or air cooling.

- Often followed by heat treatment and selective machining for critical surfaces.

Cold forging workflow

Cold forging forms metal at or near room temperature. The material resists deformation more strongly, so equipment loads and die stresses are higher—but the payoff is excellent repeatability, minimal oxidation, and a finished part that may need little to no machining.

- Start with wire/rod, cut slug, and form progressively in dies (often multi-station).

- Lubrication and die design are critical to avoid galling and to manage forces.

- May require intermediate annealing for extreme deformation steps.

Mechanical Properties and Grain Flow Differences

Both hot forging and cold forging can produce stronger parts than machining from bar stock because forging aligns grain flow with the part geometry. The difference is how strength is “built” during forming.

Cold forging: work hardening boosts strength

Cold forging introduces strain hardening, which often increases hardness and strength without additional heat treatment. As a practical reference point, cold working in steels can raise hardness on the order of ~20% (varies widely by alloy, reduction, and subsequent processing).

Hot forging: ductility during forming, properties after heat treat

Hot forging minimizes strain hardening during deformation (recrystallization “resets” the microstructure). Final properties are often achieved through controlled cooling and heat treatment, which is why hot-forged drivetrain parts (for example, connecting rods) can be optimized for fatigue performance after finishing steps.

Rule of thumb: if you want strength “for free” from deformation and can keep geometry within cold-forging limits, cold forging is attractive. If you need substantial shape change or thick sections, hot forging usually wins—and you tune properties later.

Accuracy, Surface Finish, and Machining Allowance

The biggest day-to-day difference buyers feel is how much post-processing is required. Cold forging typically reduces machining because the part comes off the press closer to net shape.

Typical tolerance and finish examples

- Cold-forged diameters are often held around 0.02–0.20 mm depending on design and process route.

- Cold-forged surface finish can reach ~0.25–1.5 µm Ra, which may eliminate secondary polishing for many functional surfaces.

- Hot-forged parts commonly need machining stock because oxidation/scale and thermal contraction introduce variability.

If your drawing includes multiple tight datums, smooth sealing surfaces, or press-fit diameters, cold forging can convert machining time into press time—often the main source of cost reduction at volume.

Cost Drivers: Tooling, Energy, Scrap, and Throughput

“Cheaper” depends on scale. Hot forging carries heating energy and scale/trim losses, while cold forging carries higher press loads and die wear but can avoid machining steps.

When hot forging tends to be more cost-effective

- Parts are large, thick, or have major section changes that would require extreme cold-forming forces.

- You already need heat treatment, so the overall thermal route is not a penalty.

- You can tolerate machining allowance on non-critical surfaces.

When cold forging tends to be more cost-effective

- High volume justifies multi-station tooling and process development.

- Machining can be reduced or eliminated on key features (threads, shoulders, bearing seats).

- Small-to-medium components like fasteners, shafts, and collars fit press capacity.

A practical way to compare is total landed cost per part: forging + trimming + heat treat + machining + inspection. In many factories, removing even a single CNC operation can outweigh higher die cost—especially when cycle time and tool wear are included.

Design Rules That Prevent Expensive Surprises

The fastest way to pick the wrong process is to ignore geometry constraints. Use these design checkpoints early—before tolerances are locked.

Cold forging design checkpoints

- Avoid extreme undercuts and very deep, narrow cavities that spike forming load.

- Plan radii and transitions to reduce die stress and prevent cracking.

- Expect limitations on highly asymmetric shapes unless using specialized tooling.

Hot forging design checkpoints

- Add draft where needed for die release and to reduce die wear.

- Account for scale and machining stock on functional surfaces.

- Specify grain flow direction if fatigue performance is a key requirement.

Tip: If the drawing requires multiple tight datums, consider designing a near-net cold-forged blank that keeps only the critical surfaces for finish machining.

A Practical Decision Checklist

Use this as a fast screen before you request quotes. If most answers land in one column, that process will usually be the more robust choice.

| If your priority is... | Leans toward Hot Forging | Leans toward Cold Forging |

|---|---|---|

| Complex shape or thick sections | Yes | Only if loads are manageable |

| Very tight tolerance / minimal machining | Less ideal | Yes |

| Best surface finish off-tool | Less ideal | Yes |

| Lower forming force / reduced die stress | Yes | No |

| Very high production volume | Depends on part size | Often strongest fit |

Bottom line: choose cold forging when you can “buy” tolerance and finish by design; choose hot forging when you must “buy” shape change and formability first.

Common Use Cases and Concrete Examples

Cold forging examples

- Automotive fasteners: high volume, consistent threads, smooth bearing faces.

- Precision collars/spacers: tight OD/ID, reduced need for grinding.

- Small gears and splines: near-net features with excellent repeatability.

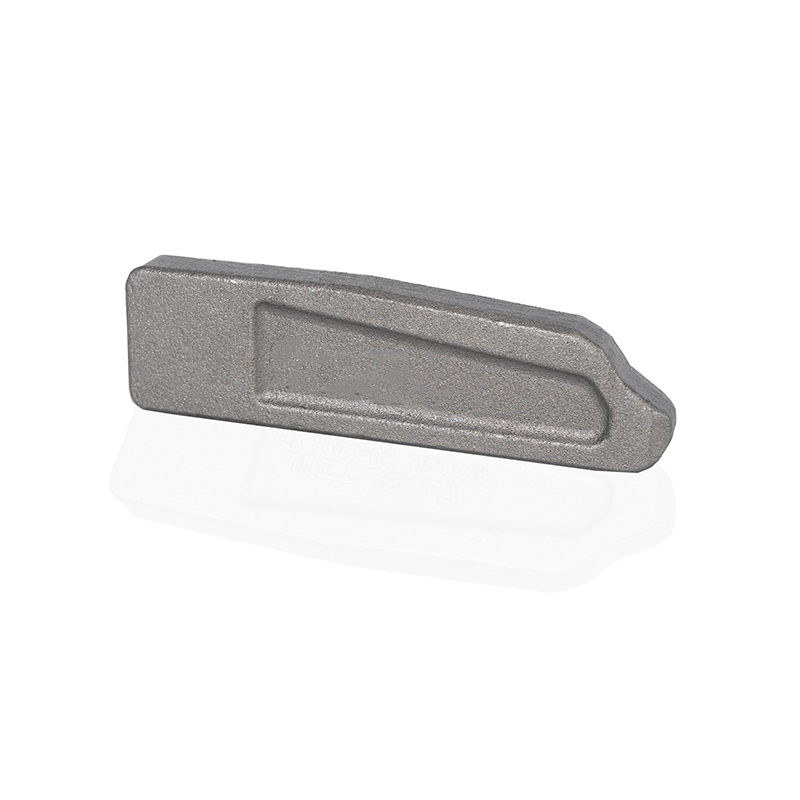

Hot forging examples

- Connecting rods: strong grain flow and robust fatigue performance after heat treat.

- Crankshafts and heavy hubs: thick sections and complex geometry that are impractical to cold forge.

- Large brackets and structural parts: cost-effective shape creation before machining key faces.

For many production programs, the best solution is hybrid: hot forge the bulk shape, then cold size or machine only the features that truly need precision.

Conclusion: Choosing Between Hot Forging and Cold Forging

Hot forging vs cold forging is a trade between formability and precision. Hot forging excels when you need major deformation, thick sections, and reliable fill in complex dies. Cold forging excels when you want tight tolerances, smooth surfaces, and reduced machining—especially at high volume.

- Pick hot forging for large/complex parts, challenging alloys, and designs where post-machining is acceptable.

- Pick cold forging for high-volume production of smaller parts where tolerance and surface finish reduce or eliminate machining.

If you share your part material, major dimensions, and the tightest tolerances, you can usually determine the best route in minutes—and avoid quoting a process that will be forced into expensive secondary operations.