Stainless Steel Grades Explained: 304 vs 316 vs 430 vs 2205

2025.12.19

2025.12.19

Industry news

Industry news

What a stainless steel grade really tells you

A stainless “grade” is a standardized recipe and property window (chemistry + microstructure + processing) that predicts corrosion behavior, strength, formability, weldability, magnetism, and cost.

At the simplest level, stainless steels resist rust because they contain enough chromium to form a thin, self-healing passive oxide film. In most standards, stainless is defined as ≥10.5% chromium by mass. More chromium generally improves oxidation resistance; additions like molybdenum and nitrogen improve chloride pitting resistance; nickel stabilizes austenite and improves toughness and formability.

However, “stainless” is not “stain-proof.” Chlorides (salt), crevices, stagnant water, high temperatures, or poor finishing can break down passivity and cause pitting, crevice corrosion, tea staining, stress corrosion cracking, or intergranular corrosion. Choosing the right grade is about matching the alloy to the exposure and fabrication realities.

How grade names work (AISI, UNS, EN 1.xxxx)

Grade labels vary by region, but they map to the same underlying material definition. You will commonly see:

- AISI/ASTM 3-digit (e.g., 304, 316, 430): widely used shorthand for common families.

- UNS (e.g., S30400, S31603): unambiguous code used across standards; “03” often indicates low carbon (e.g., 316L = S31603).

- EN (e.g., 1.4301 for 304, 1.4404 for 316L): common in Europe.

Why “L”, “H”, and stabilized grades matter

Low-carbon (“L”) grades (304L, 316L) reduce sensitization risk (chromium carbide formation at grain boundaries) after welding or high-temperature exposure, which helps prevent intergranular corrosion in many service environments.

High-carbon (“H”) grades (e.g., 304H) support better high-temperature strength (creep) but can increase sensitization risk if not managed.

Stabilized grades (321 with Ti, 347 with Nb) are designed to resist sensitization during elevated-temperature service or welding where “L” chemistry alone may be insufficient.

The stainless families you’ll actually select from

Most stainless selection decisions are really microstructure decisions. Each family has distinct trade-offs:

Austenitic (300 series: 304, 316)

- Excellent formability and toughness (even at low temperature).

- Generally non-magnetic in annealed condition (can become slightly magnetic after cold work).

- Vulnerable to chloride pitting/crevice corrosion and chloride stress corrosion cracking in hot, salty conditions.

Ferritic (400 series like 430)

- Magnetic, typically lower cost (little/no nickel).

- Good resistance to atmospheric corrosion and oxidation; limited chloride resistance versus 316 and many duplex grades.

- Often less formable than 304; weldability can be more restrictive for thick sections.

Martensitic (410, 420)

- Heat-treatable for higher hardness and wear resistance.

- Magnetic; typically lower corrosion resistance than 304/316.

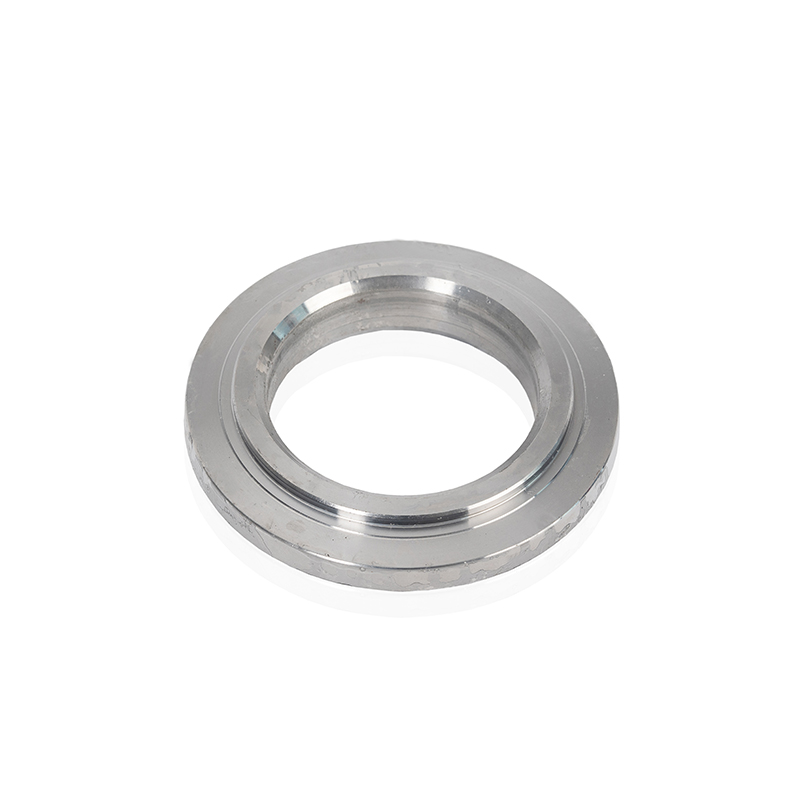

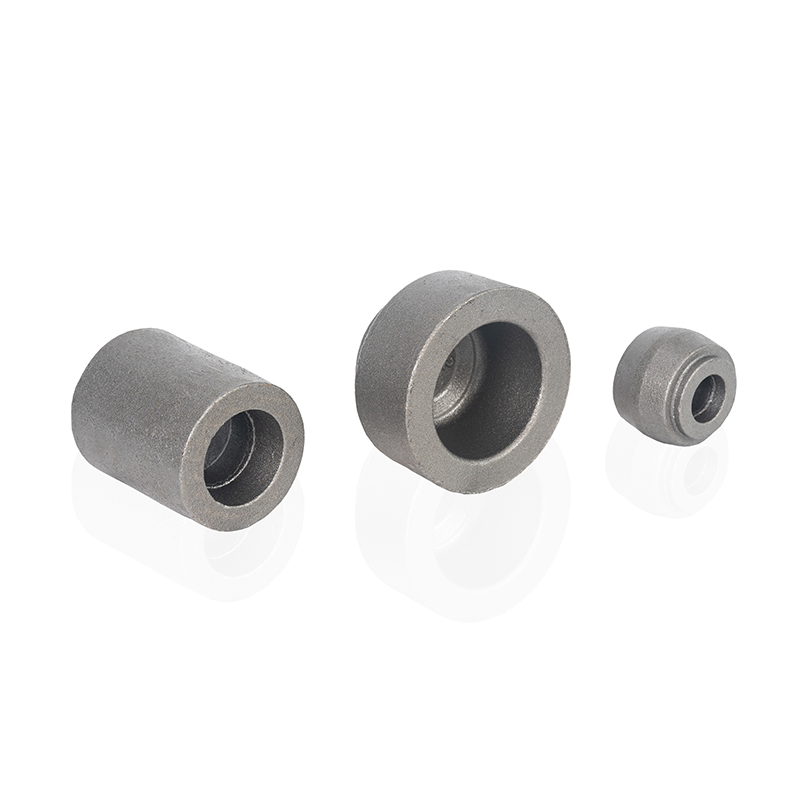

- Used for cutlery, shafts, valve parts, and wear components when hardness matters.

Duplex (2205 and beyond)

- Mixed austenite + ferrite structure: high strength and improved chloride resistance.

- Often about 2× the yield strength of 304/316 in typical conditions, enabling thinner sections.

- Welding requires tighter heat input and filler control to maintain phase balance and corrosion performance.

Precipitation-hardening (17-4PH)

- High strength via aging heat treatment; common in aerospace/industrial components.

- Corrosion resistance often between 304 and 316 depending on condition and environment.

304 vs 316 isn’t the real question: focus on chlorides and crevices

A practical stainless selection approach starts with the most common failure drivers: chloride exposure, crevices/stagnation, temperature, and surface condition. The “right” grade can change if you have a tight crevice, biofouling, intermittent wetting, or a rough finish.

Use PREN to compare pitting resistance (fast, not perfect)

A common screening metric is the Pitting Resistance Equivalent Number (PREN):

PREN ≈ %Cr + 3.3×%Mo + 16×%N

Typical ballpark PREN values (exact value depends on the specific standard range and heat chemistry):

| Grade (common) | Key additions that raise PREN | Typical PREN (approx.) | Practical implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| 304 / 304L | Cr, little/no Mo, very low N | 18–20 | Good indoors; can pit in salty/crevice conditions |

| 316 / 316L | ~2–3% Mo | 24–26 | Better for marine splash, de-icing salts, mild chemicals |

| 2205 duplex | ~3% Mo + ~0.15% N (typ.) | 34–36 | Strong option for warm chlorides and aggressive crevices |

| Super duplex (e.g., 2507) | Higher Cr/Mo/N | 40+ | For very high chloride service (seawater, hot brine) |

PREN is a comparison tool, not a guarantee. Real performance depends heavily on temperature, oxygen availability, crevices, deposits, weld quality, and surface finish. Still, for many buyers, the key takeaway is: 316 is a meaningful step up from 304 in chlorides, and 2205 is a step change again.

A quick reality check example

If you are specifying fasteners, handrails, or brackets near a coast or around pools, 304 often develops tea staining or pitting where salt deposits sit and stay wet. Switching to 316 commonly improves appearance life because molybdenum increases resistance to localized attack. If the part has tight crevices (lap joints, gaskets, thread roots) or sees warm chlorides, duplex 2205 can be the more robust choice despite higher material cost.

Common grades explained with practical “choose it when…” rules

| Grade | Family | Typical alloying cue (approx.) | Use it when… | Avoid it when… |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 304 / 304L | Austenitic | ~18–20% Cr, ~8–10.5% Ni | Indoor, food equipment, general fabrication, low chloride exposure | Coastal/pool/de-icing salt with deposits and crevices |

| 316 / 316L | Austenitic | ~2–3% Mo added to 304-type base | Marine splash, chlorides, mild chemical exposure, better crevice tolerance | Hot chlorides with high stress (risk of chloride SCC) |

| 430 | Ferritic | ~16–18% Cr, low/no Ni | Appliance panels, indoor architectural, cost-sensitive applications | Severe forming, aggressive chlorides, thick-section welding without controls |

| 410 | Martensitic | ~11.5–13.5% Cr, higher C than 304/316 | Moderate corrosion + higher hardness need (shafts, valves) | High corrosion demand or cosmetic “always bright” expectations |

| 2205 | Duplex | ~22% Cr, ~3% Mo, ~5% Ni, N added | Warm chlorides, high strength demand, chloride pitting/crevice risk | If fabrication cannot control weld heat input and procedures |

| 17-4PH | PH | Cr-Ni with Cu + Nb (aged for strength) | High strength parts where 304/316 are too soft | If maximum chloride pitting resistance is required (consider duplex/super austenitic) |

If you only remember one rule: chlorides + crevices + warmth are where “standard stainless” fails first. That is why many real-world upgrades go 304 → 316L → 2205 (or higher) as salt severity rises.

Mechanical property differences that change designs

Grades do not only differ in corrosion resistance. Strength and stiffness affect thickness, weight, and distortion. Typical room-temperature yield strength examples (order-of-magnitude; product form and condition matter):

- 304/316 annealed: around 200–250 MPa yield (many specifications list minimums near 205–215 MPa).

- 2205 duplex: commonly around 450 MPa yield minimum, enabling thinner sections for the same load.

- 17-4PH (aged): can exceed 900–1100 MPa yield depending on heat treatment condition.

Practical implication: if you are designing a bracket, frame, or pressure-containing part, duplex may reduce thickness, welding time, and deflection. That can offset higher per-pound alloy cost—provided you can fabricate it correctly.

Magnetism and cold work surprises

Ferritic and martensitic grades are magnetic. Austenitic grades are typically non-magnetic in annealed form, but cold work (bending, rolling, forming) can induce partial magnetism. If magnetism is a strict requirement (e.g., sensor interaction), specify the acceptable magnetic response rather than assuming “304 is non-magnetic.”

Welding and fabrication: where good grades fail in practice

Many stainless corrosion problems trace back to fabrication rather than the base grade. The same grade can perform very differently depending on weld procedure, heat tint removal, surface finish, and crevice design.

Use these fabrication controls as a checklist

- Choose “L” grades for welded fabrications unless you have a reason not to (helps reduce sensitization risk).

- Remove heat tint (pickling/passivation) in corrosion-critical service; heat tint can be a weak spot for pitting.

- Avoid iron contamination from carbon steel tools; free iron can rust and stain stainless surfaces.

- Design out crevices (continuous welds, sealed joints, drain paths) where chlorides or cleaning chemicals can sit.

- For duplex (2205), control heat input and interpass temperature; poor control can reduce corrosion resistance and toughness.

A simple example: why finish matters

A rough, scratched surface retains salt deposits and promotes localized attack. If appearance and wash-down performance matter, specify a finish and cleaning regimen—not only a grade. In many architectural cases, upgrading the finish (and eliminating crevices) can outperform a grade jump done without design changes.

Heat and chemical exposure: pick the right “specialist” grades

If your primary exposure is high temperature (oxidation, scaling, sensitization risk) or a specific chemical (acids, chlorinated cleaners), the common 304/316 framing may be wrong.

When heat is the main driver

- For sustained elevated temperatures with welding involved, consider stabilized grades like 321/347 (sensitization resistance in service).

- For very high temperature oxidation resistance, high-Cr/Ni grades such as 310 are often used.

- Avoid assuming 316 is “always better than 304” at temperature; selection depends on oxidation, strength, and sensitization considerations.

When chemicals are the main driver

Chemical compatibility is too broad for a single table, but you can use a safe workflow: define concentration, temperature, aeration, and contaminants; then consult chemical resistance data and specify test-backed grades. As a practical note, chloride-containing cleaners and bleach are frequent stainless killers in food service and building maintenance; in those cases, process controls and rinsing can matter as much as the alloy.

A practical grade selection matrix (environment → shortlist)

Use this as a starting point to build your specification. Always validate against your exact chloride level, temperature, cleaning chemicals, and crevice severity.

| Environment | Common failure mode | Typical shortlist | Design/fabrication note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indoor dry, low contamination | Cosmetic staining from fingerprints/cleaners | 304, 430 | Finish choice often dominates performance |

| Urban outdoor, rain-washed | Atmospheric corrosion, tea staining | 304 (mild), 316 (more robust) | Avoid crevices; specify smooth finish |

| Coastal / de-icing salts / pools | Pitting and crevice corrosion from chlorides | 316L, 2205 for harsher duty | Seal joints, remove heat tint, minimize deposits |

| Warm chlorides, stagnant/crevice-prone | Localized attack; risk of chloride SCC | 2205, super duplex, super austenitic | Control welding procedure; consider stress relief strategy |

| High strength mechanical components | Yield/deflection limits; wear | 17-4PH, 410/420 (wear), 2205 (strength + corrosion) | Specify heat treatment condition and properties |

Decision principle: if you cannot eliminate crevices or deposits and chlorides are present, upgrade the grade and upgrade the detailing—doing only one is where many projects fail.

Procurement checks: avoid “equivalent” substitutions that backfire

Substitutions happen because stainless is often purchased by shorthand grade alone. To control risk, include these checks in your specification or PO notes:

- State the full designation (e.g., 316L / UNS S31603 / EN 1.4404) to reduce ambiguity.

- Define product form and condition (sheet, plate, bar, tube; annealed, cold-worked, aged) because properties vary substantially.

- Call out surface finish requirements if corrosion appearance matters (roughness and finishing method influence deposit retention).

- For weldments, specify L-grade or stabilized grade, post-weld cleaning expectations, and acceptance criteria for heat tint.

- If chloride service is critical, consider requiring minimum PREN-related chemistry controls (or approved grade list) rather than “304 or equivalent.”

A common expensive error is accepting a lower-alloy “equivalent” for cosmetic outdoor parts. The initial cost savings often disappear once staining leads to cleaning labor, rework, or replacement.

Quick conclusion: the simplest way to choose confidently

To turn “stainless steel grades explained” into a confident choice, do this in order:

- Define exposure: chlorides (salt), temperature, wet/dry cycles, and whether deposits will sit.

- Identify crevices: threads, lap joints, gaskets, under-deposit zones, stagnant pockets.

- Pick a corrosion tier: 304 (benign) → 316L (moderate chlorides) → 2205 (warm/crevice chlorides) → higher alloys for seawater/hot brine.

- Lock fabrication controls: L-grade for weldments, remove heat tint, avoid iron contamination, specify finish.

- If strength drives thickness, consider duplex or PH grades—but specify condition and verify corrosion needs.

Bottom line: stainless grade selection is not about choosing the “best” alloy—it is about choosing the alloy that matches your chloride severity, crevice risk, temperature, and fabrication quality.